There are various locks for you to choose when developing. Each lock has different cost and use cases. In the high concurrent cases, choosing the right locks help improve system performance, otherwise your system could suffer performance loss.

Types of Locks

- Mutex (Mutual Exclusive) Lock

- Spin Lock

- Read-Write Lock

- Pessimistic Lock

- Optimistic Lock

1. Mutex

- Define: Mutex ensure ONLY ONE thread or process can access a shared recourse at a time.

For example, if there are two threads A and B. They both wanna update a shared data count. If A holds the mutex, as long as A does not release it, B would fail to acquire the mutex. Instead of continuously trying to acquire the key, B would:

- be blocked

- wait in the queue

- voluntarily yields the CPU to allow other threads or processes to execute (different from the spin lock, which we gonna talk about later).

1var mu sync.Mutex2var count = 03

4func mutexExample() {5 fmt.Println("mutexExample")6 var wg sync.WaitGroup7 wg.Add(10)8

9 for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {10 go func() {11 defer wg.Done()12 // Enter critical section13 mu.Lock()14 count++15 mu.Unlock()7 collapsed lines

16 // Exit critical section17 }()18 }19

20 wg.Wait()21 fmt.Println(count)22}cost

The blocking if failed to acquire mutex is achieved by the OS Kernel. If failed, the Kernel would set the thread to Sleep state, and the thread state would be marks as Ready when the lock is unlocked.

A context switch occurs when the CPU stops executing one thread and switches to another.

This context switch takes tens of nanoseconds to a few microseconds (depending on hardware).

If the code protected by the mutex lock executes very quickly, the time spent on context switching could exceed the time required to execute the protected code.

In this case, you may use Spin lock.

2. Spinlock

- Define: A type of lock where a thread continuously checks (spins) to see if the lock is available, instead of sleeping or being blocked.

- How it works: The thread keeps trying to acquire the lock in a loop until it succeeds.

- Use case:

- cases where the expected wait time is super short.

- kernel-level programming.

3. Read-Write Lock

- Define: Allows multiple threads to read a shared resource simultaneously, but only one single thread can write at a time.

- Use case: Reads are more frequent than writes

read-prioritize v.s. write-prioritize

-

Read-prioritize:

- A writer must wait until all readers release the lock.

- New readers arriving while a writer is waiting are allowed to process

→ Benefits: Better concurrency

→ Issue: Writer starvation

-

Write-prioritize:

- When a writer requests the lock, new readers are blocked until the writer completes its operation.

→ Benefits: Solve Writer starvation

→ Issue: Reader starvation & Lower concurrency

fair RWLock

Read & Write requests are handled in the FIFO order.

4. Pessimistic Lock

Define: A pessimistic lock assumes that conflicts between threads or transactions are likely, so it prevents conflicts by locking the resource upfront.

Example: Mutex

5. Optimistic Lock

Define: An optimistic lock assumes that conflicts between threads or transactions are rare, so it allows operations to proceed without acquiring a lock. It verifies later if conflicts occurred.

How to build it:

- CAS (Compare And Swap) mechanism

- Version Number mechanism

1) CAS

-

CAS has three operations:

- Memory location

Vfor read & write - Expected value

Afor comparison - New value

Bplanned to write

- Memory location

-

How it works:

If the value at the Memory location

V== Expected valueA, update the value toB. Otherwise, do nothing -

Code example:

1type Counter struct {2value int323}45// Increment performs an atomic increment using Compare-And-Swap (CAS)6func (c *Counter) Increment() {7for {8current := atomic.LoadInt32(&c.value) // Read the current value atomically9newValue := current + 1 // Compute the new value10if atomic.CompareAndSwapInt32(&c.value, current, newValue) {11// Successfully updated the value12break13}14// Retry if the CAS operation failed due to a race condition15}6 collapsed lines16}1718// Value returns the current counter value19func (c *Counter) Value() int32 {20return atomic.LoadInt32(&c.value) // Read the value atomically21} -

Cons:

- ABA Issue

- Limited to Single Variable: CAS operates on a single variable at a time, making it less suitable for complex data structures that involve multiple fields.

- High Retry Cost: In highly contested environments, CAS can lead to frequent retries if other threads modify the value simultaneously.

- Spin-Waiting: busy-waiting consumes CPU cycles.

ABA Issue

-

Define: It occurs when a value in memory changes temporarily to another value and then back to its original value, making it appear as if the value has never changed.

-

Example:

In a lock-free stack, the top of the stack is managed using a CAS operation. Suppose:

- Thread 1 reads the stack top as

Node A. - Thread 2 pops

Node A(makingNode Bthe new top) and then pushesNode Aback. - Thread 1 attempts to update the stack top using CAS, believing it still points to

Node A.

Although the CAS operation succeeds, the stack has changed, leading to inconsistencies or corrupted data structures.

- Thread 1 reads the stack top as

-

Issue:

- Memory Reuse: If the value A refers to a memory location that was temporarily repurposed, the CAS operation may unknowingly operate on outdated or invalid data.

- Data Structure Integrity: In dynamic structures like stacks, queues, or linked lists, intermediate changes can lead to structural corruption if not detected.

-

Solutions:

- Attach a Version Number: checks both the

valueand theversion

- Attach a Version Number: checks both the

2) Version Number

-

How it works:

- Add a

versionattribute in the data to represent version number of the data.

- Read Phase: A thread reads the resource and its version number.

- Perform Operations: The thread computes updates assuming no conflicts.

- Validation Phase: Before committing, the thread checks if the version number matches the initial read.

- Commit Phase:

- If the version matches, the update is applied, and the version is incremented.

- If not, the update fails, and the thread retries.

- Add a

-

Code example:

1// UpdateBalance tries to update the account balance using optimistic locking2func (a *Account) UpdateBalance(amount int32) bool {3for {4// Load the current balance and version atomically5currentBalance := atomic.LoadInt32(&a.balance)6currentVersion := atomic.LoadInt32(&a.version)78// Compute the new balance9newBalance := currentBalance + amount1011// Attempt to update both balance and version atomically12if atomic.CompareAndSwapInt32(&a.version, currentVersion, currentVersion+1) {13// Successfully updated the version, now update the balance14atomic.StoreInt32(&a.balance, newBalance)15return true9 collapsed lines16}17// If CAS fails, retry as the version has changed18}19}2021// GetDetails returns the current balance and version for display22func (a *Account) GetDetails() (int32, int32) {23return atomic.LoadInt32(&a.balance), atomic.LoadInt32(&a.version)24} -

Cons:

- Retry overhead

- Complex Validation Logic: With multiple fields or nested updates, ensuring consistency requires carefully managing version numbers.

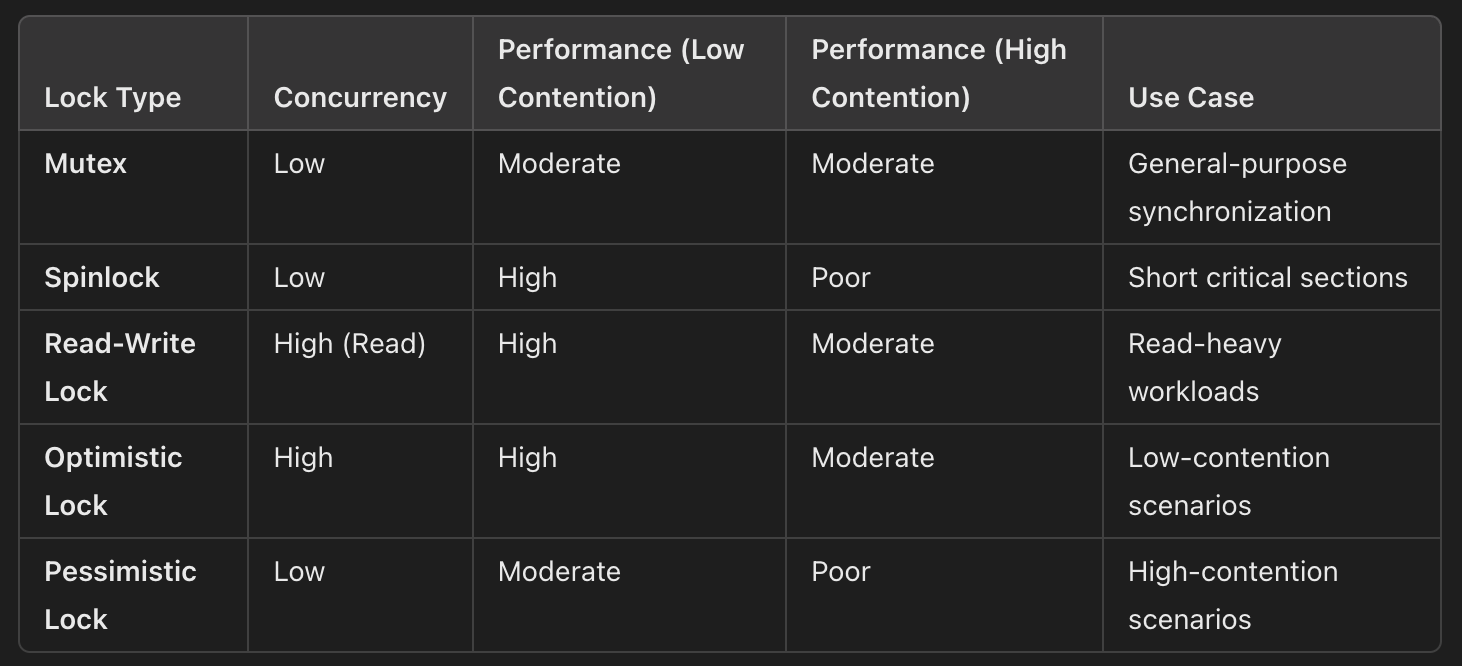

Summary