0. Goroutine Scheduler

When discussing “scheduling,” the first thought is often the scheduling of processes and threads at the operating system (OS) level. The OS scheduler coordinates multiple threads in the system, assigning them to physical CPUs according to specific scheduling algorithms. In traditional programming languages such as C’s concurrency is primarily achieved through OS-level scheduling. The program is responsible for creating threads (commonly using libraries like pthread), while the OS handles the scheduling. However, this conventional method of implementing concurrency comes with various limitations:

- Complexity: easy creation but hard to exit.

- High scaling cost: although threads have lower costs than processes, we still cannot create a large number of threads. Because each thread consumes the considerable resources, and the cost of context switching between threads by the operating system is also substantial.

1. About Threads

Goroutines are based on threads. Let’s take a look at three thread models:

- Kernel-level threads

- User-level threads

- Two-level threads (hybrid model)

The biggest difference between these models lies in how user threads correspond to Kernel Scheduling Entities (KSE). KSE is a kernel-level thread, the smallest scheduling uint in the OS.

1) User-level threads

User threads and kernel thread KSE follow a many-to-one (N:1) mapping model. Multiple user threads typically belong to one single process, and their scheduling is handled by the user’s own thread library (at user-level). Operations such as thread creation, destruction, and coordination between threads are all managed by the user-level thread library without the need for system calls. For instance, the Python’s coroutine library gevent uses this approach.

All the threads created in one process are dynamically bound to the same KSE at runtime. In other words, the OS is only aware of the user process and has no awareness of the threads within it (because the OS kernel sees the process as a whole).

Since thread scheduling is handled at the user level, it avoids the need for context switching between user mode and kernel mode and thus this approach is lightweight.

However, this model has an inherent drawback: it cannot achieve true parallelism. If one user thread within a process is interrupted by the CPU due to a blocking operation, all threads within that process will also be blocked.

2) Kernel-level threads

User-level threads and kernel thread KSE follow a one-to-one (1:1) mapping model. Each user thread binds to one kernel thread, and their scheduling is handled by the OS’s kernel. Most thread libraries, such as Java’s Thread and Cpp’s thread, encapsulates the kernel threads, and each thread created by the process binds to its own KSE.

The pro of this model is achieving true concurrency through the OS’s kernel thread and its scheduler for fast context switching.

The con is its high resource cost and performance issue.

3) Two-level threads

Kernel-level threads and kernel thread KSE follow a many-to-many (N

) mapping model. This model combines the advantages of both user-level and kernel-level threading models while avoiding their respective drawbacks:-

Multiple KSEs per Process: Allow multiple threads within the same process to run concurrently on different CPUs.

-

Shared KSEs:

Threads are not uniquely bound to specific KSEs. Multiple user threads can share the same KSE.

When a KSE becomes blocked due to a blocking operation, the remaining user threads in the process can dynamically rebind to other available KSEs and continue running.

2. G-P-M model in Go

2.1 Intro

Each OS thread has a FIXED-size memory (typically 2MB) for its stack. This fixed size is too large and too small to some extents. While it is too large for some simple tasks, like generating periodical signals, it is too small for some complex tasks, like deep recursions. Therefore, goroutine is born.

Each goroutine is an independent executable unit. Instead of being assigned with a fixed memory stack size, goroutine sticks with dynamic adapting approach:

- A goroutine’s stack starts with 2 KB and dynamically grows and shrinks as needed, up to max 1 GB on 64-bit (256 MB on 32-bit)

This dynamic stack growth is FULLY MANAGED by Go Scheduler. And Go GC periodically reclaims unused memory and shrinks stack space, further optimizing resource usage.

2.2 Structures

1) Goroutine (G):

Each Goroutine corresponds to a G structure, which stores Goroutine’s runtime stack, state, task function. Gs can be reused, but are not execution entities themselves. To let Gs to be scheduled and executed, it must be bound to a P.

2) Logical Processor (P):

- From the perspective of

Gs, Ps function like a “CPU” - itGs must be bound to aP(via the P’s local run queue) to be scheduled for execution. - For

Ms,Ps provide the necessary execution context (memory allocation state, task queues, etc.) - # of

Ps determines the max number ofGs that can run concurrently (assume # of CPUs ≥ # ofPs). # ofPs is determined byGOMAXPROCSand max # ofPs is 256.

Analogy: Think G as a task to be completed, M as a factory worker, and P as the workstation. For a task to be scheduled, it must be assigned to a P.M does not carry tools with them. Instead they go to P to pick up the tools (memory cache) and tasks (G) needed for the job, and return to P once completed.

3) Thread (M)

The abstraction of thread. M represents the actual computational resource that performs the execution. After binding to a valid P, M enter the scheduling loop.

- The scheduling loop works as:

- Fetch a

Gfrom the global queue, the local queue of the boundP, or the wait queue. - Switch to the

G’s execution stack and run theG’s task function. - Perform cleanup using

goexitand return toMto repeat the process.

- Fetch a

M does not retain G’s state, which allows Gs to be rescheduled across different Ms. The # of M is adjusted by Go Runtime. To prevent creating too any OS threads from overwhelming the system schedule, the max # of Ms is 10,000.

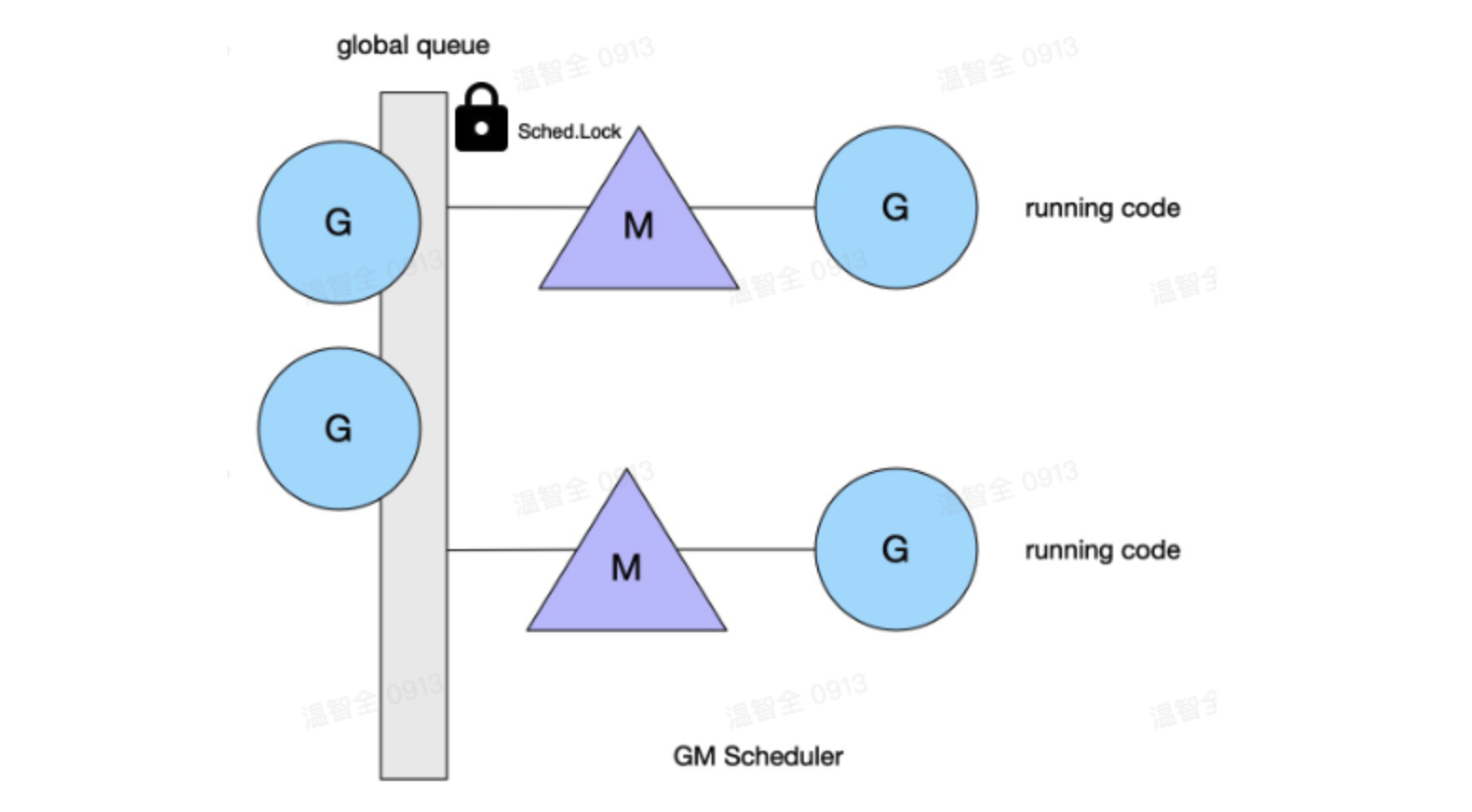

2.3 Depreciated goroutine scheduler

In the initial versions of Go, the scheduler uses G-M model, without P. Since the model has own one global queue for G, it suffers issue of:

- One Global Mutex: For

Ms, executing or returning aGrequires access to the global G queue. Since there are multipleMs, a global lock (Sched.Lock) is required to ensure mutex and synchronization. - Goroutine Passing Issue: Goroutines in the runnable state are frequently passed between different

M→ delay and overhead. - Memory Caching by Each

M: EachMmaintains its own memory cache → excessive memory usage and poor data locality. Syscall-Induced Blocking: Intense blocking and unblocking of worker threads caused bysyscallinvocations result in additional performance overhead.

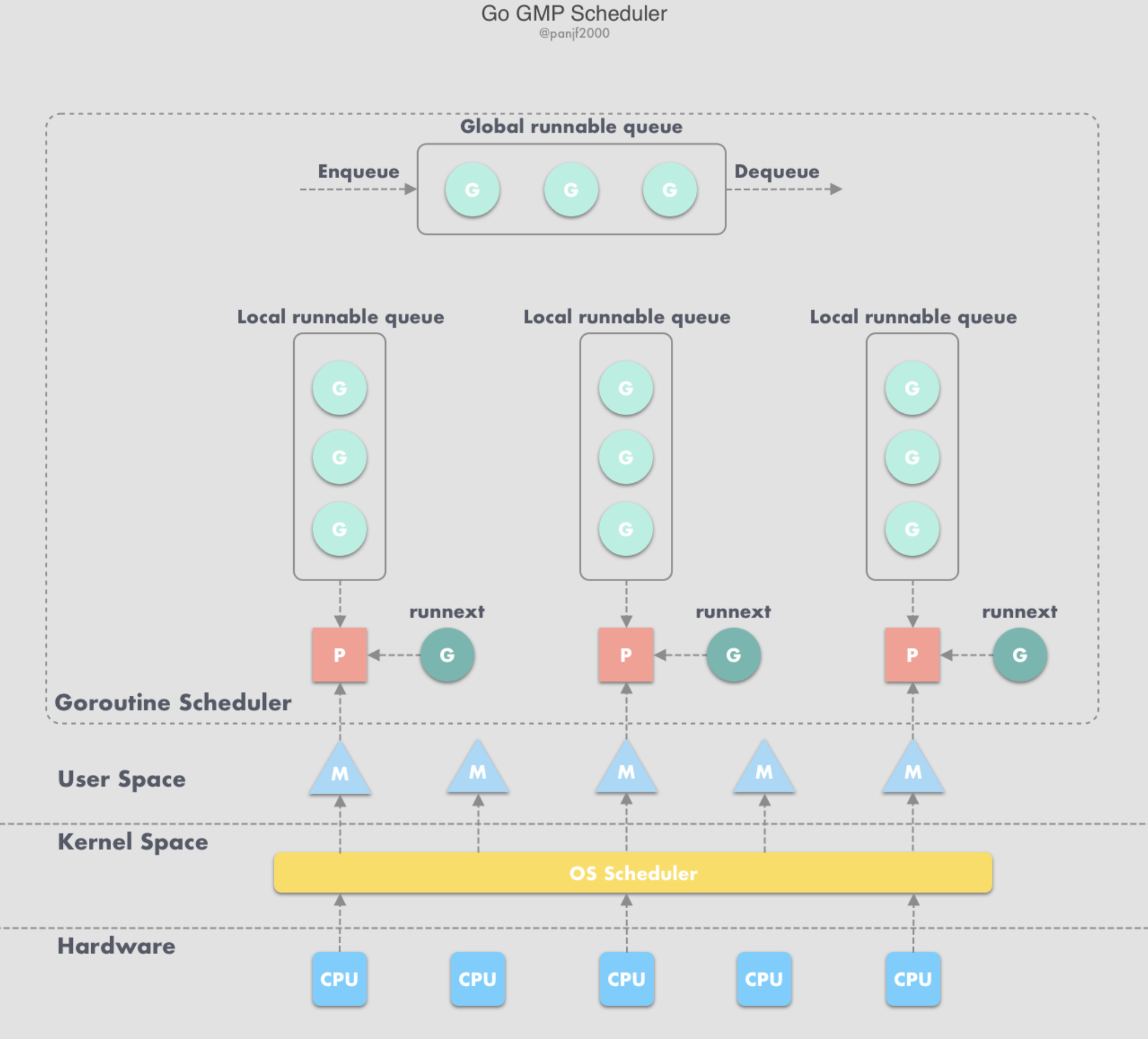

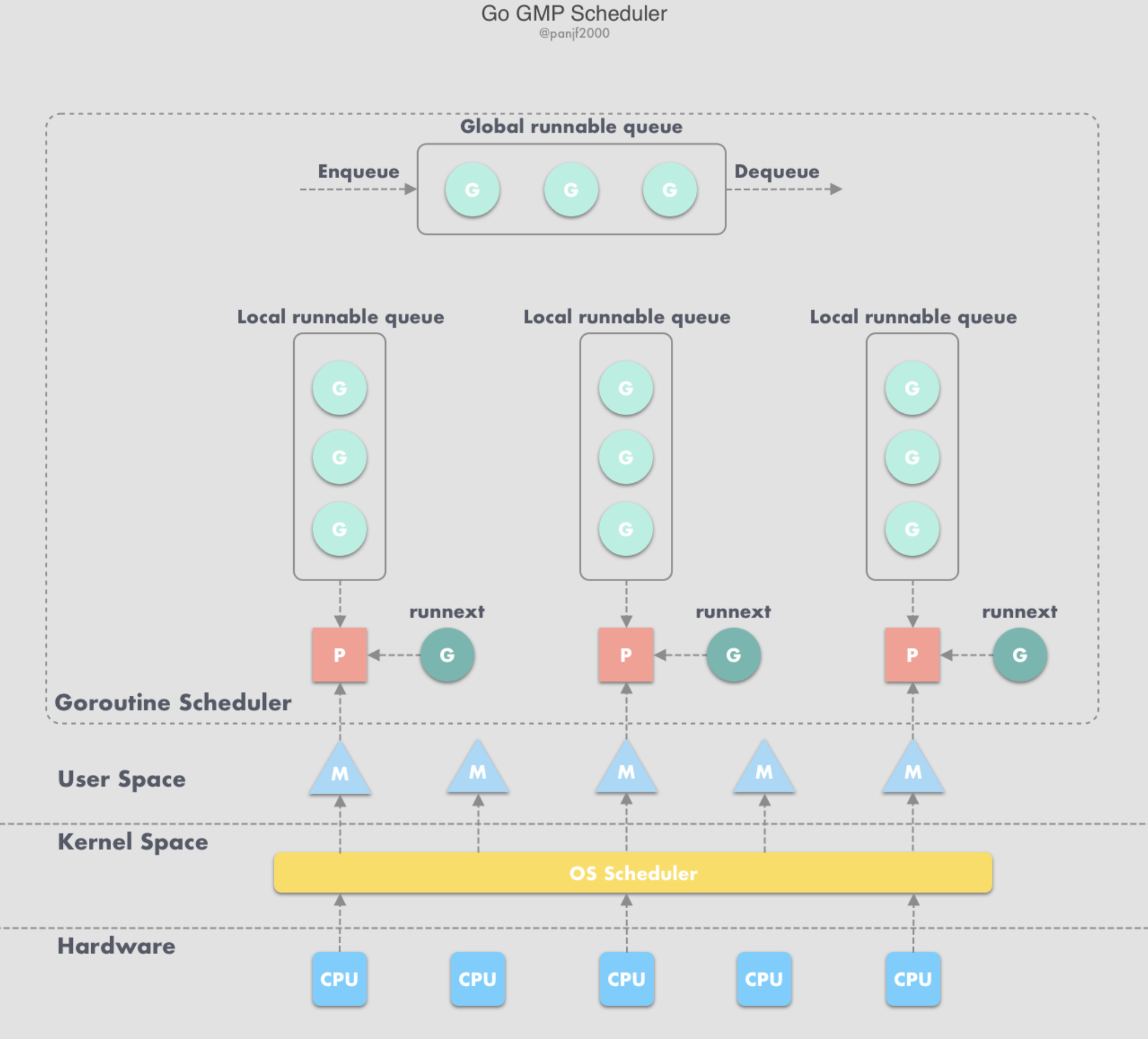

2.4 G-P-M

1) working-stealing mechanism

Due to the poor concurrency performance of the G-M model, G-P-M and the scheduling algorithm Working-Stealing Mechanism were introduced:

- Each

Pkeeps a local run queue to storeGthat are ready to execute. - When a new

Gis created or transitions to a runnable state, it is added to the local run queue of the associatedP. - When a

Gfinishes executing on anM,Premoves it from its local queue.- If the queue is not empty, the next

Gin the queue is executed. - If the queue is empty, it attempts to steal

Gs from other threads bound to the sameP, rather than terminating the thread.

- If the queue is not empty, the next

2) components

- Global queue: Store waiting-to-run

Gs. The global queue is a shared resource accessible by any P and is secured by a mutex. P’s Local Queue: Contain waiting-to-run Goroutines, but with a limited capacity (256 top). When a new GoroutineGis created, it is initially added to theP’s local queue. If the local queue becomes full, half of its Goroutines are moved to the global queue.PList: AllP’s are created at program startup and are stored in an array.

3) exceptions

Go Runtime would execute another goroutine when the goroutine is blocked due to the following four cases:

- Blocking syscall

- Network input

- Channel operations

- Primitives in the sync package

-

User state blocking/ waking:

When goroutine is blocked by channel ops, the corresponding

Gwould be moved to a wait queue (such as a channel’swaitq). The state ofGchanges fromrunningtowaiting.Mwould skips thisGand attempts to execute the nextG.If there are no runnable

Gs available:- The

Munbinds from thePand goes into asleepstate. - he

Pis now free to assign runnable tasks to otherMs.

When the Blocked Goroutine is Woken Up:

- When the blocked

Gis woken up by anotherG, it is marked as runnable - The runtime would attempts to add this

Gto:- The runnext slot of the

PwhereG2resides - If the

runnextslot is full, it is added to theP’s local queue. - If the local queue is full, it is added to the global queue.

- The runnext slot of the

- The

-

Syscall blocking:

When a

Gis blocked due to a system call:G’s state changes to_Gsyscall.Mexecuting thisGenters ablockedstate.

Handling the Blocked

M:- The blocked

Munbinds from theP. - The

Pbecomes available and:- Binds to another idle

Mif one exists and continues the execution on its local queue. - If no idle

Mis available but there areGs in theP’s local queue, the runtime creates a newMto bind to thePand execute thoseGs.

- Binds to another idle

When the System Call Completes:

Gis marked as runnable and attempts to acquire an idlePto resume execution.- If no idle

Pis available,Gis added to the global queue.

References

https://dev.to/aceld/understanding-the-golang-goroutine-scheduler-gpm-model-4l1g

https://tonybai.com/2017/06/23/an-intro-about-goroutine-scheduler/

https://wenzhiquan.github.io/2021/04/30/2021-04-30-golang-scheduler/